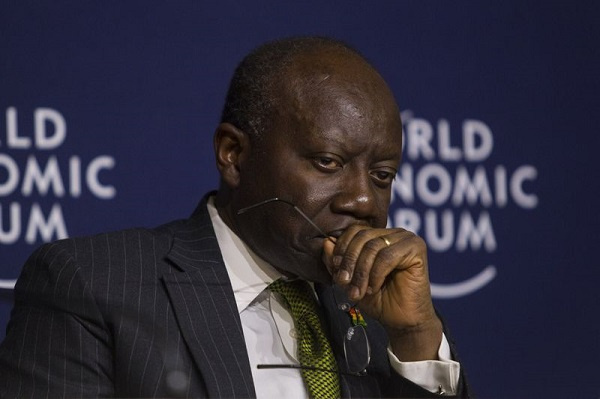

Ghana’s Finance Minister, Ken Ofori-Atta, has defended the operational capacity of central banks to function with negative equity, emphasising that such losses incurred by central banks should not be viewed in the same light as commercial banks or enterprises.

His remarks came in response to criticisms and calls for the resignation of the Governor of the Bank of Ghana, Dr. Ernest Addison, following a reported GHS 60 billion loss.

In an article defending the Bank of Ghana’s actions during unprecedented global events, Mr Ofori-Atta cited examples of central banks in other countries that have faced similar losses.

He argued that in modern economic policy, central banks can sustain losses as they support economic recovery and meet their policy objectives.

Mr Ofori-Atta highlighted that many central banks, including those in Jamaica, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, the Philippines, Singapore, Turkey, and the UK, have incurred losses while still achieving their policy objectives. He said historical instances also reveal that some central banks have operated with negative equity without compromising their effectiveness.

The Finance Minister further noted that global events like the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war have pushed more central banks into negative equity. For instance, central banks in Chile, Czech Republic, Israel, and Mexico have experienced years of negative equity.

Mr Ofori-Atta provided examples of central banks facing losses, such as the Reserve Bank of Australia, which fell into negative equity in 2022 due to bond valuation losses, and the US Federal Reserve Bank, which declared a negative equity position in April 2022.

He explained that central banks’ focus has shifted from direct targets of money supply to interest rates as operational targets. This shift he explained enables central banks to play more interventionist roles in the economy, as demonstrated during the 2007 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 era, where significant quantitative easing was undertaken by G7 countries.

Mr Ofori-Atta emphasised that the primary objective of a central bank is not to generate profits but to manage itself as a financially sustainable institution, especially in extraordinary times.

The Finance Minister urged citizens not to perceive the Bank of Ghana’s actions as punitive but as part of its efforts to support the greater public good.

Read Ofori-Atta’s opinion below

There is an anonymous quote that says “banks are to the economy what the heart is to the human body. They cycle necessary capital through the whole and they are barely noticed until pressure, necessity, or crises.”

In much the same way, our Central Bank these past almost seven years has been prudent, strong, resilient and functioning efficiently, and been barely noticed until the interruption of unprecedented global events. Our Central Bank’s assets have grown almost in tandem with the size of our financial sector and economy.

From GHS53b in 2016, the Bank’s assets have grown by nearly one and half to GHS126b as at the end of 2022. The foundation has never been conspicuous – our revenue has more than doubled since 2016, with total revenue increasing from GHS32b in 2016 to GHS96.7 (endDecember 2022).

The size of our economy has also more than doubled from a GDP value of GHS219.6b in 2016 to an estimated GHS610.2b by the end of 2022; and more pragmatically the number of active contributors on the SSNIT register has increased from 1.3 million in 2016 to over 1.8 million in 2022.

We can all attest to the progress made in digitization, infrastructure, the armed forces and police, public spending on education, agriculture (cocoa and PFJ), health, and school feeding among others. Indeed, spending on the education sector including our universities, second-cycle institutions and basic schools collectively constitute about 20% of tax revenue – and includes compensation, goods and services, and GETFund spending on infrastructure, while the health sector consumes about 8-10% of tax revenue, among others.

However, the vision for and progress in social mobility and economic freedom is often in budget conflict with short-term macroeconomic volatility, where the activist roles of fiscal and monetary policy, and if blessed with a Keynesian benefactor or fiscal windfall, must be deployed to ensure that these gains are not eroded.

This is especially the case in instances where the volatility is mainly induced by cataclysmic events such as pandemics and geo-politics – the controls are often outside the remits of small open economies with independent central banks like Ghana.

It is within this context that since 2017 and especially between November 2019 and now, both the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Ghana have shown the strongest collaboration yet to reset the financial architecture and to keep the economy strong.

In managing its balance sheet, the Bank of Ghana issues currency, conducts foreign exchange operations, invests its own funds, engages in emergency liquidity assistance, conducts monetary policy operations, and liquidity management, last but not least, for a developing country, serves as a banker to Government which role may include bridge financing to support budget, in line with the applicable laws.

In essence, this makes the central bank balance sheet, in the long run, central to its operations. However, as many central banks, including Bank of Ghana, moved away from pursuing quantitative targets of monetary policy towards price targets, dominance of the Central Bank’s balance sheet as the key metric has waned in many economies and in academic literature as well.

In practice, many central banks have incurred losses, and we can cite as examples, the Bank of Jamaica, the central banks of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, the Philippines, Singapore, Turkey, and UK. Historically, some central banks have operated with negative equity (as a result of losses) yet fully met their policy objectives, as long as they remain policy solvent.

The pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war have reinforced and increased the number of Central banks that have moved into negative equity and have thrown light into this ‘new normal.’ Thus, the Central Banks of Chile, Czech Republic, Israel and Mexico have experienced years of negative equity. The Reserve Bank of Australia fell into negative equity in 2022 due to valuation losses on its bond holdings, and the bank stressed that it will not affect its mandate or operational efficiency. And unheard of in the modern financial setup, the German central bank, that citadel of fiscal purity, recorded a loss in 2022.

The US Federal Reserve Bank in April 2022 also declared a negative equity position, on account of the rapid rise in rates that began in 2022, renewed interest expenses on commercial bank reserves deposits, and low income on its security holdings, including US Government securities.

In fact, as indicated by the Brookings Institution, “the Fed’s cumulative losses came to more than $52 billion as at the end of April 2022, exceeding its paid-in capital and surplus, and in effect, leaving it in negative equity.”

(I cite these examples just to make the point that hitherto unheard of things have been happening in central banks around the world recently.)

Accordingly, as the focus shifts from direct targets of money supply to interest rates as operational targets, the framework for analysing central bank balance sheets has shifted, enabling central banks to play more interventionist roles in the economy than before. As seen during the 2007 global financial crisis and the COVID era, over $16 trillion of quantitative easing (QE) was reported to have been spent by the G7 countries.

The modern economic policy consensus is clear: central banks can and do run on negative equity and they can make losses to support economic recovery; and these losses will not be counted as failure as in commercial banks and enterprises. In fact, as some critics of the Central Bank in our country do observe, the primary objective of a central bank is not to make profit but to be managed as a financially sustainable institution.

We must in these extraordinary times deploy all the instruments we have available and sail together through this odyssey. The call for us as Citizens, is not to be seen as punishing the Bank of Ghana for pitching up to support the greater public good!

It is probably a good time to recall the wise words of the late Professor P.A. V Ansah that even as we educate and inform, we must foster national cohesion because “…national cohesion is the foundation upon which any and everything is built.”

The Government’s debt operations that commenced in 2022, and executed this year, has had a significant impact on Bank of Ghana’s balance sheet while reducing the amount of money spent on interest payment for the

Government. As of 2022, the Central Bank held about GHS42.3b of Government’s domestic debt, out of the total (domestic) debt stock of GHS194.3b. This debt holding, in addition to others, resulted in a loss impairment provision of about GHS48b for the Bank in 2022.

As indicated by the IMF, the BoG was the loss absorber for the debt exchange to ensure that in light of the concessions to other domestic bondholders, its burden share of the debt exchange will enable the economy to still achieve the overall objectives of the Exchange – the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme will ensure the NPV of the stock of public sector debt is halved from the then 105 percent of GDP (later recalculated as 89%) to 55 percent of GDP by 2028, thereby putting the country on a sustainable debt trajectory.

As indicated by the Board of Directors of the Bank in their 2022 annual reports, all efforts will be made to restore the balance sheet of the Bank in the medium term, continue to improve the efficiency of their operations, and resort to the Government for recapitalization over the medium to long term if necessary. There is, therefore, no need for a direct attack on the leadership of the Central Bank.

As the Minister for Finance, I do have opinions about the reforms needed to strengthen the governance of many financial institutions including the Bank of Ghana. But this requires a positive and sober national debate on the governance structure; should we, for example, revisit a separate chairmanship and governorship (such was the case prior to governor Dr. Agama’s years) and whether our democracy and institutional experience support Governors playing both board leadership and management roles as enshrined in our laws.

We also need to have the discourse for policy clarity on what the operational independence of the central bank implies, especially in a Lower-Middle Income Country and transformational economies such as ours. I do personally believe that central banks must have independence in executing their monetary policy mandate especially if it is based on a price target, where the Government sets the price targets, and Central Banks, in our case, BoG, independently uses its operational tools to achieve it.

Source: classfmonline.com